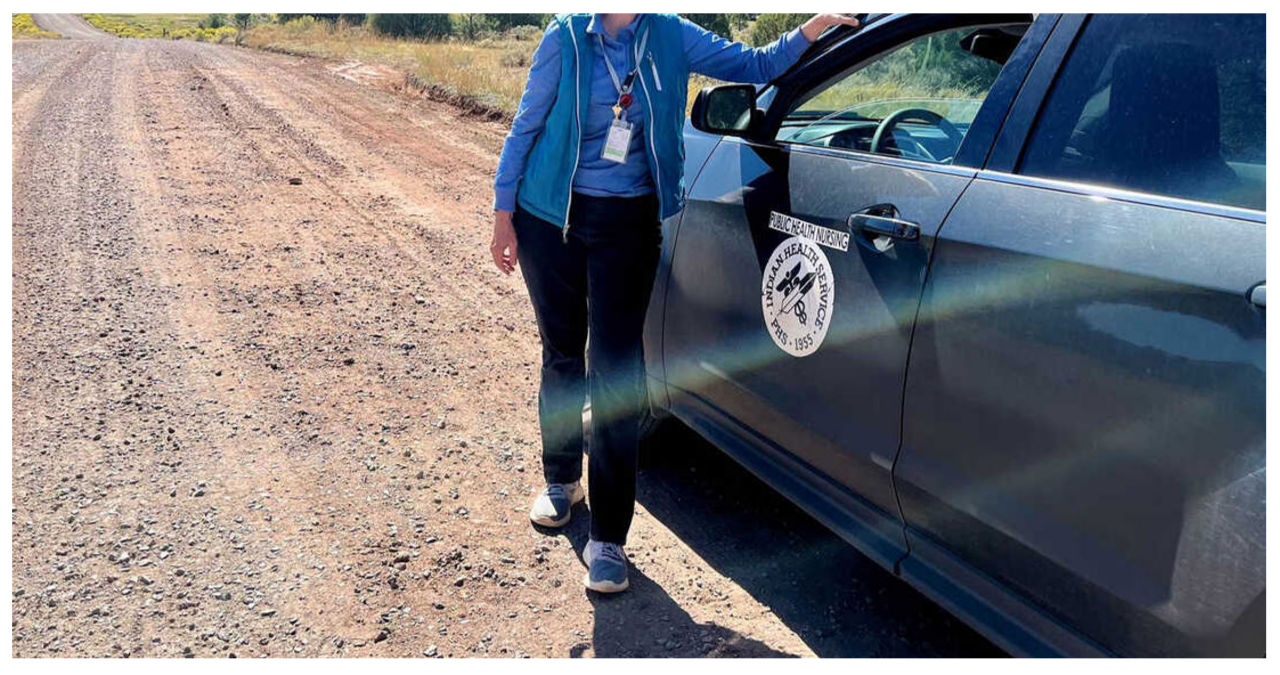

Melissa Wyaco, based in Gallup, New Mexico, oversees a team of approximately two dozen public health nurses. These dedicated professionals tirelessly navigate the vast expanse of the Navajo Nation to locate individuals who have either tested positive for or been exposed to a disease that was once on the verge of elimination in the United States: syphilis.

Infection rates in this region of the Southwest are some of the highest in the nation. The 27,000-square-mile reservation spans parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. These rates are far worse than anything Wyaco, the nurse consultant for the Navajo Area Indian Health Service and a member of Zuni Pueblo located approximately 40 miles south of Gallup, has witnessed in her 30-year nursing career.

Syphilis infections have seen a significant increase in recent years, reaching a 70-year high in 2022, as reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This alarming rise coincides with a shortage of penicillin, the most effective treatment for this infection.

Congenital syphilis, a condition where syphilis is transmitted from a pregnant person to a baby, has also seen a surge in cases. If left untreated, it can lead to various serious complications such as bone deformities, severe anemia, jaundice, meningitis, and even death. According to the CDC, in 2022 alone, there were 231 stillbirths and 51 infant deaths attributed to syphilis, out of the 3,761 reported cases of congenital syphilis.

Infections have surged throughout the United States, but no group has suffered more than Native Americans. According to the CDC’s data published in January, the incidence of congenital syphilis among American Indians and Alaska Natives was three times higher than that of African Americans and nearly twelve times higher than that of white babies in 2022.

Meghan Curry O’Connell, the chief public health officer at the Great Plains Tribal Leaders’ Health Board, who is based in South Dakota, expressed her frustration with the persistence of a disease that was once anticipated to be eradicated. She emphasized the effectiveness of the available treatment and lamented the fact that the disease continues to pose a threat despite the presence of a successful remedy.

The rate of congenital syphilis infections among Native Americans in 2022, at 644.7 cases per 100,000 people, is now similar to the rate of 651.1 per 100,000 for the entire U.S. population in 1941, before doctors started using penicillin to treat syphilis. The national rate has since dropped to 6.6 in 1983.

According to O’Connell, the Great Plains Tribal Leaders’ Health Board, along with tribal leaders from North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Iowa, have requested Federal Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra to declare a public health emergency in their respective states. By doing so, they aim to enhance staffing, funding, and access to contact tracing data throughout the region.

According to O’Connell, syphilis poses a grave threat to infants due to its highly contagious nature and the severe consequences it can have. She emphasizes the urgent need for individuals to actively engage in on-site efforts to combat the disease.

Public health resource diverted for COVID care

In 2022, the state of New Mexico had the highest rate of congenital syphilis among all states. On the other hand, South Dakota had the second-highest rate of congenital syphilis, but it reported the highest rates of primary and secondary syphilis infections, which are not passed on to infants.

In 2021, South Dakota ranked second-worst in the nation (after the District of Columbia) in terms of its rate, according to the most recent demographic data available. The state’s large Native population had the highest numbers.

In an October news release, the New Mexico Department of Health highlighted a concerning trend: cases of congenital syphilis in the state have surged by 660% over the past five years. In 2017, there was only one reported case, but by 2020, the number had risen to 43. Shockingly, in 2022, the number of cases further escalated to 76. This dramatic increase in congenital syphilis cases is alarming and calls for immediate attention.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the situation. Jonathan Iralu, the Indian Health Service chief clinical consultant for infectious diseases, based at the Gallup Indian Medical Center, explained that “Public health across the country got almost 95% diverted to doing COVID care. This was a really hard-hit area.”

During the early stages of the pandemic, the Navajo Nation witnessed the highest COVID rate in the entire United States. Iralu suspects that individuals displaying symptoms of syphilis may have refrained from seeking medical attention due to the fear of contracting COVID. However, he believes that it would be unjust to attribute the persistent high rates of syphilis, as well as the transmission of infections from mothers to their babies during pregnancy, solely to the pandemic, as these issues have persisted for four years now.

Native Americans, more than any other racial or ethnic group, tend to reside in rural areas, far removed from hospital obstetric units. Consequently, they often face challenges in accessing timely prenatal care, if they receive it at all. This lack of early prenatal care leads to providers being unable to conduct syphilis testing and treatment before delivery.

In New Mexico, nearly a quarter of patients (23%) did not begin receiving prenatal care until the fifth month of pregnancy or later, or received fewer than half of the recommended number of visits based on the infant’s gestational age in 2023. This percentage is significantly higher than the national average of less than 16%.

A mistrust of health care providers

Native Americans face an increased risk of transmitting a syphilis infection during pregnancy due to inadequate prenatal care. This risk is particularly significant as syphilis infections are equally prevalent among both men and women in Native communities. In contrast, in all other ethnic groups, men are at least twice as likely to contract syphilis, mainly due to the higher susceptibility of men who engage in sexual activities with other men.

According to O’Connell, the reason behind the disproportionate impact of syphilis on women in Native communities remains unclear.

“The Navajo Nation lacks adequate maternal health services,” expressed Amanda Singer, a Diné (Navajo) doula and lactation counselor in Arizona, who also serves as the executive director of the Navajo Breastfeeding Coalition/Diné Doula Collective. In certain areas of the reservation, patients are required to travel over 100 miles to access obstetric services. Singer further highlighted, “There is a significant proportion of pregnant women who do not receive prenatal care throughout their entire pregnancy.”

According to her, the reason behind this is not just a lack of services, but also a deep-rooted mistrust towards healthcare providers who do not comprehend Native culture. Additionally, there is concern among some individuals that healthcare providers might disclose information about pregnant patients who use illegal substances to law enforcement or child welfare authorities.

But there are other reasons contributing to this problem as well. One major factor is the decrease in the number of healthcare facilities available in the Navajo area. Over the past decade, two labor and delivery wards in the region have closed down. This issue is not unique to the Navajo area; in fact, a recent report revealed that over half of rural hospitals in the United States no longer provide labor and delivery services.

Singer and her network of doulas strongly advocate for the expansion of prenatal care in rural Indigenous communities in New Mexico and Arizona as a means to address the syphilis epidemic. According to Singer, a potential solution could involve the provision of prenatal care services, including midwifery, doula support, and lactation counseling, directly to families in the comfort of their own homes.

According to O’Connell, the sharing of data between tribes and various government agencies, such as state, federal, and IHS offices, differs greatly across the nation. This has presented an additional obstacle in addressing the epidemic within Native communities, including her own. O’Connell’s Tribal Epidemiology Center is currently striving to gain access to South Dakota’s state data, as it fights to combat the issue at hand.

In the Navajo Nation and the surrounding area, Iralu shared that infectious disease doctors from the Indian Health Service (IHS) hold monthly meetings with tribal officials. He strongly suggests that all IHS service regions establish regular gatherings involving state, tribal, and IHS providers, as well as public health nurses. The goal is to ensure that every pregnant individual in these areas undergoes proper testing and receives necessary treatment.

IHS now advises conducting syphilis testing on all patients annually, with pregnant patients undergoing testing thrice. Moreover, the organization has broadened the availability of rapid and express testing and introduced a new antibiotic called DoxyPEP. This medication can be taken by transgender women and men who have sex with men within 72 hours after sexual activity and has proven to reduce syphilis transmission by an impressive 87%. However, one of the most notable advancements made by IHS is the provision of testing and treatment services in the field.

Today, the public health nurses under Wyaco’s supervision now have the ability to test and treat patients for syphilis in the comfort of their own homes. This is a significant improvement from just three years ago when Wyaco herself was a part of the nursing staff and such services were not available.

Iralu suggested a different approach: instead of forcing the patient to come to the penicillin, why not bring the penicillin to the patient?

IHS doesn’t employ this tactic for every patient, but it has proven effective in treating individuals who may transmit an infection to their partner or unborn child.

Iralu anticipates a growth in street medicine within urban areas and van outreach in rural areas in the upcoming years. This expansion will bring more testing opportunities to communities. Additionally, there will be efforts to make testing more accessible by providing tests through vending machines and mail delivery to patients.

“This marks a significant departure from our previous approach,” he remarked. “However, I firmly believe that it aligns with the direction in which the future is headed.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that specializes in producing comprehensive journalism on health issues. It serves as one of the core operating programs at KFF, which is a trusted and independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.