In the late summer of 2022, the Mississippi state government received a routine report from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) evaluating its utilization of federal funding for water infrastructure. The EPA’s assessment concluded with the reassuring words: “no findings,” indicating that Mississippi’s expenditure of funds was deemed appropriate and in accordance with regulations.

On August 29, the following day, a staggering number of 180,000 residents in the Jackson area found themselves without access to clean drinking water. In response to this dire situation, Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves and Jackson Mayor Chokwe Lumumba swiftly declared a state of emergency.

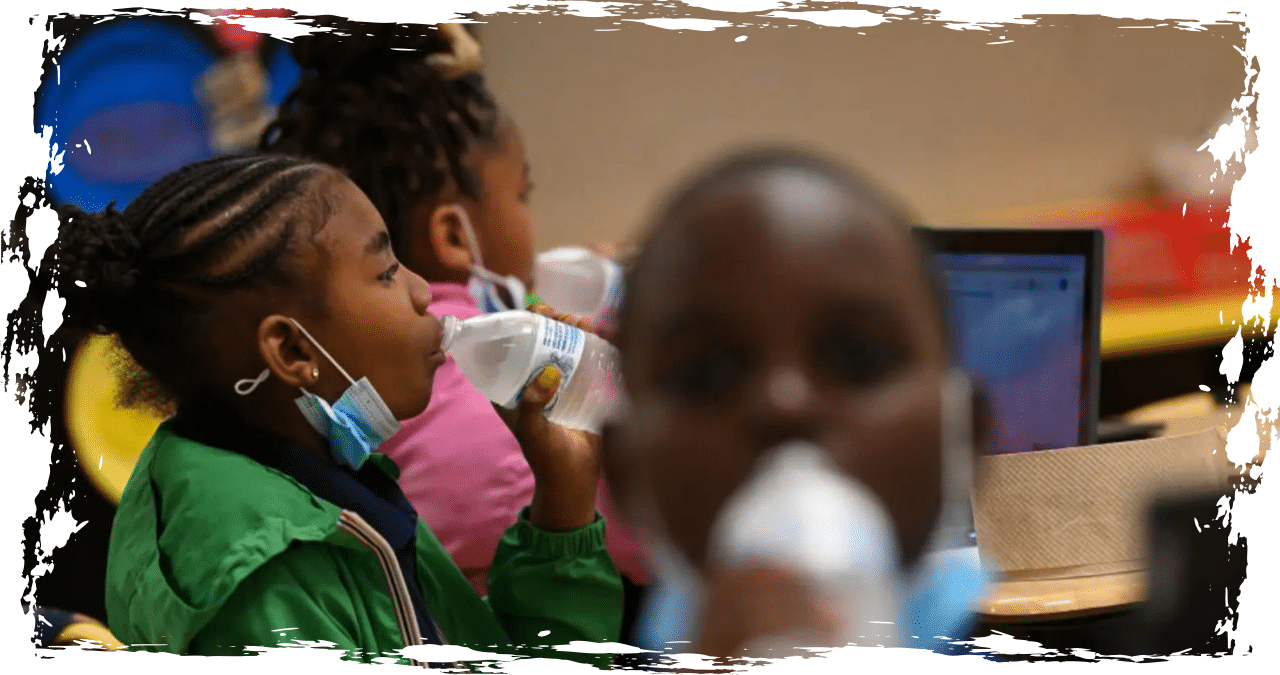

The region experienced a deluge of more than twelve inches of rain, resulting in the flooding of the Pearl River. This river, originating approximately 75 miles northeast of Jackson and flowing south to the Gulf Coast, caused significant damage. The excessive rainfall overwhelmed Jackson’s main water treatment plant, resulting in a loss of water pressure throughout the system. As a result, residents, hospitals, and fire stations were left without access to safe drinking water. Many homes were completely without water. The sight of the National Guard distributing cases of bottled water to residents in long queues made national headlines. However, a recent report by researchers at the Project for Government Oversight (POGO) challenges the EPA’s conclusion and suggests that Jackson was just one heavy rainfall away from a public health crisis.

Nearly two years have passed, and thousands of residents in Jackson are still grappling with the persistent issues of low water pressure and discolored brown water. Although the state and local governments have shouldered much of the blame for this crisis, a report by POGO sheds light on the role played by the EPA. In their investigation, the researchers unearthed a disconcerting pattern: EPA officials were aware that insufficient federal funds were being allocated by the state for infrastructure upgrades in Jackson, yet they neglected to document these practices in their assessments.

According to Nick Schwellenbach, one of the researchers on POGO’s report, EPA oversight plays a crucial role. He emphasizes that although the agency cannot compel states to allocate funds in a specific manner, its oversight can influence and encourage states to adopt best practices. The investigation brings attention to a communication breakdown within the EPA. While the agency has taken proactive measures to address drinking water issues in Jackson, such as filing a lawsuit in 2020 for violating the Safe Drinking Water Act, its supervision of the state’s utilization of federal funds for water infrastructure improvements has been restricted.

According to Schwellenbach, EPA oversight has the potential to prevent disasters. He mentioned that while the EPA was informing Jackson that he was not in compliance with federal law, they were not taking the additional step of reaching out to the state to inquire about their efforts to assist.

Decades of neglect had taken a toll on Jackson’s infrastructure long before the heavy rains triggered the city’s water crisis. This decline is not unique to Jackson but is a common trend among mid-sized cities like Memphis, St. Louis, and Pittsburgh. As the white, middle-class residents moved to the suburbs in the late twentieth century, tax dollars for infrastructure improvements became scarce. The city’s demographic makeup also underwent significant changes, with the Black population increasing to over 80% from 50% in the 1980s, and a quarter of the residents living in poverty. These shifts in demographics led to a majority-Black and Democrat city council, which, in turn, caused friction with the predominantly white Republican state government by the 1980s.

In 1996, the Safe Drinking Water Act underwent amendments by Congress, which introduced a program allowing municipalities to receive federal funding for the purpose of updating their struggling water infrastructure. This program, known as the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund, is overseen by state environment departments. These departments review applications from local governments and distribute funding in the form of loans on an annual basis. As part of its responsibility, the EPA produces yearly reports to track the allocation of funds. The agency describes these audits as integral to the “circle of accountability,” providing guidance for funding decisions and program management policies. However, in the case of Jackson, the reports appear to have merely served as a rubber stamp for Mississippi’s management of the fund, as noted by POGO researchers.

The EPA’s oversight of the fund has been flagged by multiple arms of the agency over the past decade. The Office of Inspector General, the internal watchdog, has found issues with the reports dating back to 2011 and as recently as last year. In a 2014 document, the OIG highlighted that the EPA’s audits often fail to ensure that federal dollars from the fund are allocated to communities with the greatest public health need or to disadvantaged communities, which, as POGO researchers pointed out, are often one and the same. Furthermore, in a 2017 internal memo that was revealed in the POGO report, EPA officials mentioned an unspent pool of money in Mississippi, which represented untapped potential for protecting public health. Despite this, the agency’s regional office issued a positive audit to Mississippi that year.

Mississippi has consistently received substantial funds from the Fund, totaling over $260 million between 2017 and 2021. However, the city of Jackson has not been able to benefit from these allocations. According to a civil rights complaint filed with the EPA in 2022 by the NAACP, Jackson has only received loans three times throughout the entire 25-year history of the program. In contrast, the Bear Creek Water Authority in predominantly rural and white Madison County has received funds nine times during the same period. It is worth noting that the NAACP complaint was recently dismissed by the EPA.

According to Governor Tate Reeves, the Mississippi state government denies claims that Jackson has received less funding compared to other parts of the state. In 2022, Governor Reeves stated that there is no factual basis to suggest an “underinvestment” in the City. However, the researchers from POGO pointed out that the Governor’s statement fails to acknowledge the state’s historically strict loan program and the city’s reluctance to take on additional debt.

According to Schwellenbach, one issue is that the EPA does not actively release its oversight reports to the public. In order to conduct their investigation, Schwellenbach’s team had to submit a freedom of information request to obtain hundreds of records. Along with examining the EPA’s program assessments for various states, the researchers also analyzed internal EPA memos and inspector general reports. Additionally, they conducted interviews with EPA staff members to gain a thorough understanding of the agency’s awareness of the conditions in Jackson.

According to Janet Pritchard, the director of water infrastructure policy for the Environmental Policy Innovation Center, the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) reviews of state programs are often shrouded in mystery. She describes them as a “black hole” with limited transparency and accountability. While some states have made efforts to redefine terms like “disadvantaged communities” and update policies governing the distribution of state revolving fund awards, it is unclear to what extent the EPA is actively engaged in these processes. Johnnie Purify, an EPA staffer in the Region 4 office overseeing Mississippi, expressed support for making EPA oversight reports public, believing that they would be beneficial to external parties and the general public.

The people of Jackson have been severely impacted by the EPA’s failure to inform Mississippi about the unequal allocation of federal funds. As a result, the city continues to face the issue of discolored water flowing out of taps, causing significant disruptions to residents’ daily lives. Even a powerful thunderstorm can now easily disrupt the fragile water infrastructure, leaving the community in turmoil for weeks on end. Furthermore, this ongoing crisis has also contributed to the city’s rapid decline in population, as reported by the Clarion Ledger, making Jackson the fastest shrinking city in the country.

In November 2022, a federal judge selected Ted Henifin, an engineer, to oversee the city’s water system. Initially, local advocates were optimistic about Henifin’s ability to improve the system, given his expertise. However, as time passed, they grew frustrated with what they perceived as a lack of transparency in his decision-making.

In December 2022, the Biden Administration made an announcement stating that $600 million would be allocated in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to Jackson for the purpose of repairing its water system. This significant amount of funding gives Henifin the authority to decide how it should be used. As a result, in early 2023, Henifin took the initiative to establish JXN Water, a private company dedicated to updating the city’s water system.

However, this move has raised concerns among the public, who fear that the water system may be privatized in the future. This has also sparked worries about transparency, as private corporations are not obligated to comply with public disclosure laws. Despite repeated requests from local advocates, there has been no response regarding the data on water sampling efforts.

Furthermore, frustration grew among local advocates when Henifin unexpectedly terminated Tariq Abdul-Tawwab, a long-time community advocate and the sole Black employee at JXN Water. This decision has only added to the concerns and skepticism surrounding the management of the city’s water system.

Last summer, Henifin informed a federal judge that, to his knowledge, there were no health risks associated with the drinking water, even though there were reports of some residents still experiencing discolored tap water resembling tea. This statement has further raised doubts about the accuracy and reliability of the information provided by Henifin regarding the water quality in Jackson.

The situation continues to be a matter of concern for the residents, who remain apprehensive about the future of their water system and the transparency of the decision-making process.

After being fired, Abdul-Tawwab took on the role of managing the ground support team for the Mississippi Rapid Response Coalition. This team consists of emergency responders who assist the community with any needs that the state or city may not be able to address. According to Abdul-Tawwab, residents often reach out to request help with various issues, such as leaky roofs or burst sewage pipes. However, the most common concern is the quality of the drinking water. Members of Abdul-Tawwab’s team primarily focus on delivering bottled water and filters, as well as conducting tests on residents’ taps to detect heavy metals like lead or bacteria such as E-Coli. These tests frequently yield positive results, indicating contamination.

Abdul-Tawwab, while avoiding the specifics of his dismissal, expressed his discontent with Henifin’s handling of Jackson’s financial resources. He noted that journalists often visit Jackson to highlight the deteriorating infrastructure but rarely inquire about the allocation of federal funds designated for the welfare of the residents.

Abdul-Tawwab expressed his concern over the measures taken by the state of Mississippi to prevent Jackson from receiving the necessary support. He emphasized that it’s crucial for readers in the United States of America to grasp this reality.

Henifin, in an email to Grist, affirmed his belief that Jackson’s water is clean. He emphasized that JXN Water consistently conducts tests in compliance with federal permitting requirements. Additionally, he reassured that any brown water complaints received through their call center are promptly investigated, although such occurrences are infrequent.

According to the spokesperson, JXN Water ensures transparency by posting all Quarterly Reports on their website, hosting public meetings to address questions, and actively participating in community group meetings when invited. He emphasized that transparency is not a concern for the organization.

However, many residents of Jackson have pointed out that the water that comes out of their faucets is in a significantly different condition compared to the clean water that is produced by the city’s treatment plants. Despite requests for thorough testing of the extensive network of pipes, these inquiries have often been left unanswered. Brooke Floyd, a director at the People’s Advocacy Institute and a member of the Mississippi Rapid Response Coalition, expressed her skepticism regarding Henifin’s claim that residents are not reporting contaminated water to JXN Water’s call center. According to Floyd, the ground team frequently receives reports of water that contains visible debris or substances floating in it.

Floyd recognized the proactive approach of JXN Water in sharing its reports on Facebook. However, he emphasized that advocates are not only concerned about transparency in terms of quarterly paperwork. They also want to actively participate in decision-making processes. Recently, a federal judge granted the request of advocates from the Mississippi Poor Peoples’ Campaign and the Peoples’ Advocacy Institute to join the EPA’s lawsuit against the city of Jackson. By securing a seat at the table during the legal proceedings, they hope to influence the allocation of federal funds and prevent any potential privatization threats.

According to Floyd, once Henifin, the DOJ, and the EPA depart, the consequences of their actions or lack thereof will be endured by the community. She drew attention to the ongoing issue in Flint, Michigan, where the water crisis, initiated over ten years ago, remains unresolved.

According to Schwellenbach, a POGO researcher, the situation in Jackson serves as a symbol of a larger issue and could potentially indicate more dire consequences if the EPA doesn’t increase its oversight. He cited the example of Memphis, where the aging water system is facing strain due to climate-related impacts and a lack of investment over the years. While the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law has provided significant federal funding to assist cities in upgrading their water infrastructure, it is crucial for the EPA to enhance its involvement to ensure that these funds are effectively utilized to benefit communities.

“The EPA should have taken a more proactive approach in alerting and pressuring the states to take the necessary action,” he expressed. “It is crucial that we learn from this unfortunate incident to prevent similar crises from occurring in the future.”