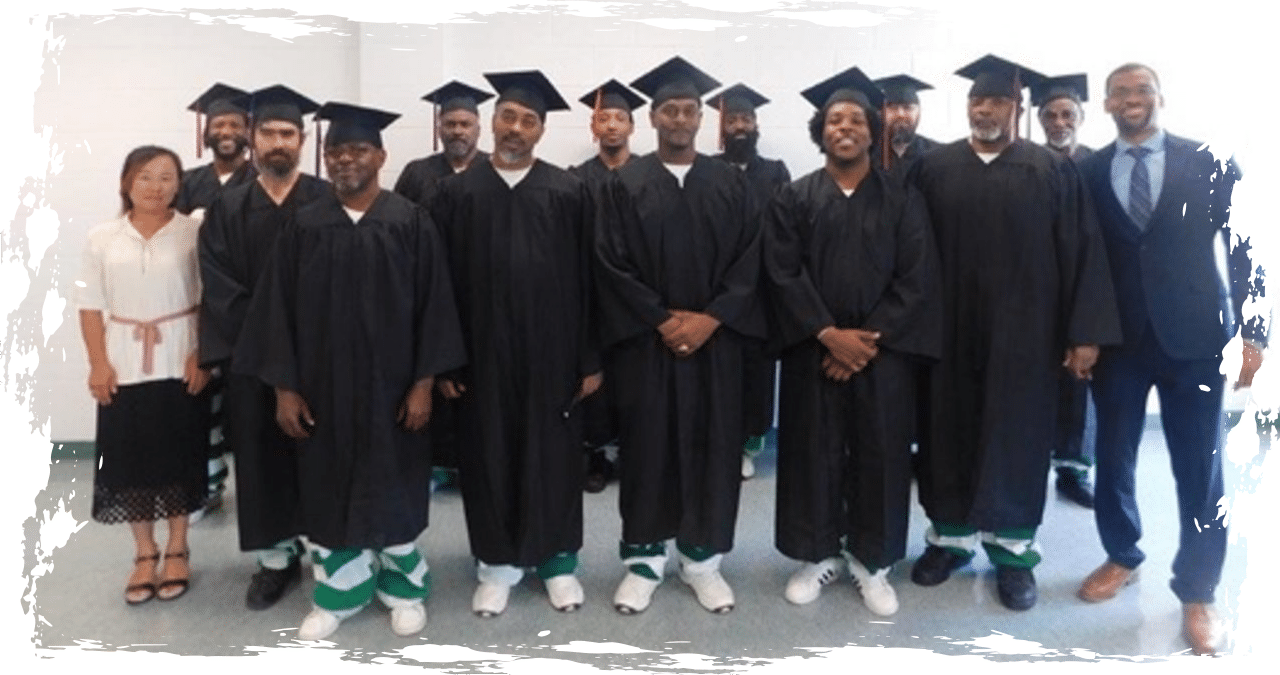

A program in Mississippi is offering increased access to educational opportunities for incarcerated individuals. The University of Mississippi’s Prison-to-College Pipeline Program allows students at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman to enroll in college courses and earn credits. The program, founded in 2014, aims to provide equitable education and intellectual growth for this underserved population, going beyond reducing recidivism rates.

The courses offered through the program are team-taught and student-centered, with a focus on humanities-based subjects such as history, English, African American studies, and even topics like Shakespeare and the history of Africa. There is also a course currently being taught that helps students learn how to write about their own lives.

Mississippi has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country, with over 1,000 people in prison for every 100,000 residents. The College of Liberal Arts at the University of Mississippi and the Laughing Gull Foundation from North Carolina provide funding for the program. The university and provost have even waived tuition fees, which has allowed the program to expand its offerings.

The program, which initially served a relatively small number of students per year (around 35 to 50), is now looking to double its capacity. Patrick Elliot Alexander, the program’s director, expressed gratitude for the support and expressed the hope that they can serve more incarcerated individuals in the future.

Barry Carter, a former student of the program, shared his experience and gratitude. He mentioned that the Prison-to-College Pipeline Program gave him the self-confidence to believe in himself and see that his life wasn’t over, even though he was a convicted felon in his mid-50s. It opened his eyes to the opportunities that were still available to him.

In 2016, the program expanded to include women at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility, thanks to the efforts of Alexander’s colleague, Otis Pickett. However, the COVID-19 pandemic presented challenges that made it difficult for the program to continue its operations.

In North Carolina, the state prisons house the majority of the 57,000 people behind bars. However, there is a new proposal that aims to address this issue, but it requires approval from Congress. The proposed Public Safety and Prison Reduction Act offers incentives to states to reevaluate their sentencing policies and reduce their prison populations.

The Brennan Center for Justice, which is behind this proposal, highlights state prisons as the central problem in mass incarceration, as they hold 87% of the incarcerated population in the country. Hernandez Stroud, senior counsel at the Brennan Center, argues that Congress can help break the cycle of excessive imprisonment by providing funding as an incentive for states to shrink their prison populations and implement more humane alternatives.

Earlier this year, the Legislative Oversight Committee on Justice and Public Safety in North Carolina discovered that the state’s current prison population has already surpassed projections not expected until 2027. The Brennan Center’s proposal places a strong emphasis on accountability and community involvement. States would be required to collaborate with researchers and local stakeholders, including formerly incarcerated individuals, to monitor the impact of their reforms. This approach could also address systemic issues within the criminal justice system, such as wrongful convictions and harsh sentencing.

Stroud believes that this legislation has the potential to send a powerful message to the nation, transcending partisan politics and focusing on delivering public safety while promoting a fair and humane justice system.

The proposal suggests that if the 25 states with the largest prison populations could reduce them by 20%, nearly 180,000 fewer individuals would be incarcerated. However, the Public Safety and Prison Reduction Act has not yet been introduced in Congress, and its estimated cost of $1 billion may pose a challenge to its implementation.

Groups in North Carolina are coming together to address the issue of how people are punished for minor offenses. Their goal is to break the cycle where small offenses can have major consequences, such as jail time.

One initiative, led by Black Voters Matter in partnership with the group Growing Real Alternatives Everywhere, is the introduction of Saturday warrant clinics. These clinics provide a lifeline for individuals who are unable to attend court during the week.

Anza Becnel, the warrant clinic manager for Black Voters Matter, explained that the clinics aim to bridge the gap between the court system and the community. The ultimate goal is to create a better balance between the offense committed and the punishment received.

Becnel observed that a significant percentage of city residents have traffic warrants and lower-level misdemeanor warrants. The warrant clinics help overcome barriers that prevent people from attending court, such as transportation issues or fear of arrest. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, low-level offenses and other non-felony offenses account for about 25% of the daily jail population in the country.

The groups have already hosted three successful clinics, assisting approximately 250 people in resolving their issues on the spot. In addition to the individual benefits, Becnel argued that warrant clinics play a crucial role in reducing the backlog in court systems. Participants often receive immediate resolutions or new court dates through these clinics. Becnel emphasized that the success of this approach lies in its community-centered focus.

During the clinics, attendees can enjoy a welcoming atmosphere with a food truck and a DJ. Unlike regular court sessions during the week, individuals can freely use their cellphones without fear of law enforcement. Becnel outlined the positive aspects of the warrant clinics, creating an environment that is more accessible and less intimidating for participants.

The groups are also planning to expand their warrant clinic model to other states, such as Georgia, Alabama, and Texas. Each clinic will be tailored to meet the specific needs of the community it serves.