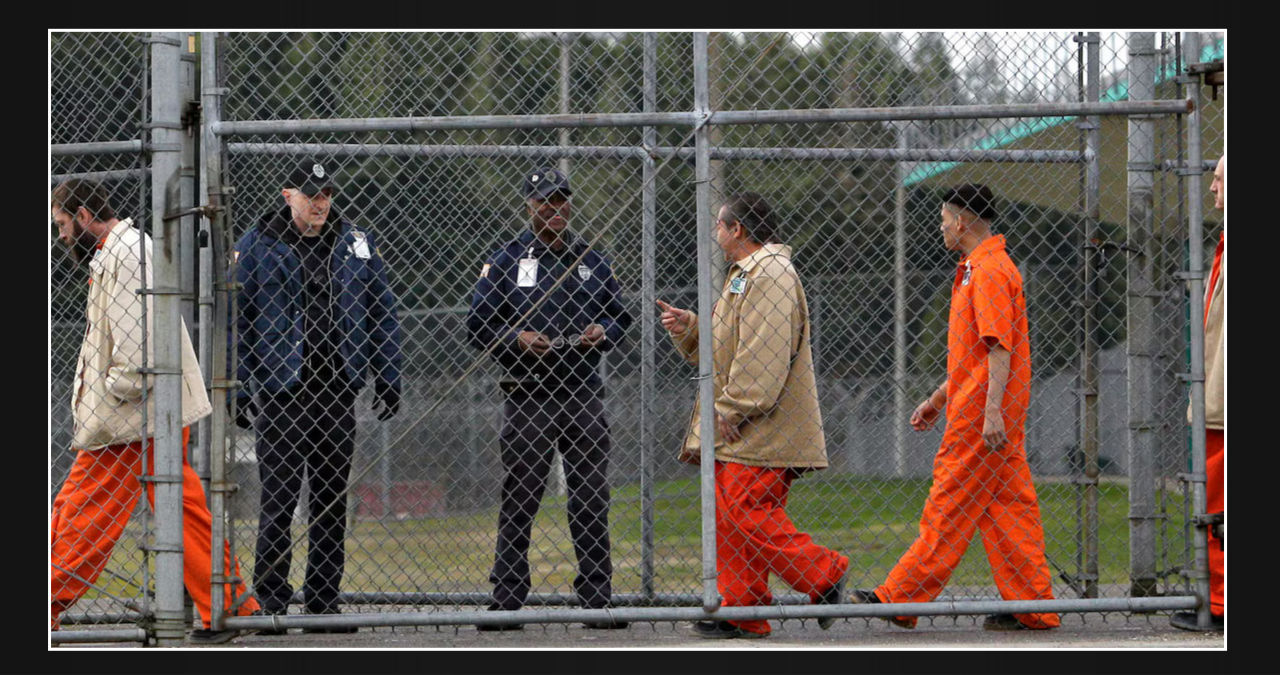

When February 2011 photo of the Washington Corrections Center in Shelton is observed, inmates can be seen walking past correctional officers. Recent data has shown that almost 30% of Washington prison inmates who were released during fiscal year 2023 were granted their freedom after their set release date, causing difficulties in readjusting to civilian life and costing taxpayers millions of dollars. Among all facilities, the Shelton prison had the highest number of delays, with some of them being the longest among all the prisons in the state, according to information obtained from the DOC.

The photograph displayed above is credited to Elaine Thompson of the Associated Press.

During the summer of 2019, Antonio Castillo decided to hitchhike the last 280 miles of his journey back home from the Washington Corrections Center in Shelton to his grandmother’s house in Okanogan County.

Upon his release from prison, he found himself without a clear direction. After being placed in the intensive management unit for several months due to a conflict with a corrections officer, he had little time outside of his cell, leaving him unable to plan for the future. At the age of 25, he was serving the final months of a one-year sentence for possession of drugs and a stolen firearm. Without a job or even a ride home, Castillo faced a difficult road ahead.

Castillo faced an additional challenge despite having time to prepare for his release. He was completely unaware of when he was going to be released, as he revealed to InvestigateWest, stating, “I was totally in the dark.”

Castillo had no idea that his earned release date had already passed by a month when he left the Washington Corrections Center.

Castillo argues that if he had been given a specific release date, he could have made some basic arrangements for his return home. However, due to the uncertainty surrounding his release date, he never had the opportunity to prepare himself adequately.

It’s a common occurrence for inmates to face uncertainty upon their release from prison. InvestigateWest conducted a data analysis that revealed nearly one-third of the approximately 5,000 individuals released from Washington prisons in fiscal year 2023 were held past their earned release date. The earned release date takes into account good behavior and credit for time served in county jails before their conviction. While the median delay was around one month, some individuals experienced delays that lasted well over a year. These delays make it challenging for inmates to plan their new lives and cost taxpayers millions of dollars.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the share of inmates released late increased in Washington, despite the shrinking prison population. This was observed even after the Department of Corrections had released many inmates who were resentenced due to the landmark Blake decision of the Washington Supreme Court in 2021, which effectively decriminalized drug possession until a new statute was passed by the Legislature.

While some delays in the release of inmates were inevitable, there were several avoidable ones too. For example, an inmate who was convicted of arson might find it difficult to secure housing after their release, and in some cases, DOC needs to approve it. However, inmates and reentry support providers cite instances where the delays could have been avoided. For instance, an inmate was kept back because a counselor failed to issue a legally required notice to the victims until the eleventh hour. Another inmate had to wait past their release date for the sentencing documents to arrive via mail from a county court.

Although Gov. Jay Inslee of Washington previously criticized the DOC for incorrectly releasing some inmates too early, the magnitude of delayed releases has not been given equal attention. It is worth noting that these issues are not exclusive to Washington. The Nebraska Department of Correctional Services has also recently come under fire for holding inmates in custody for longer than what state lawmakers had intended.

Inmates are encouraged to follow prison rules and take part in educational and work programs through earned release dates. These dates allow them to reduce their sentence by months or even years. Otherwise, the alternative is a maximum expiration date that signifies the end of their entire prison sentence.

Planning for an inmate’s return to the outside world is crucial, and their earned release date serves as the foundation for this process. Upon reaching their release date, most inmates will be set free and must transition back into society.

When inmates are held beyond their earned release date, it can be devastating for their plans for employment, housing, and support networks. This can greatly reduce their chances of successfully reintegrating back into society.

Leandru Willie, a case manager with Native American Reentry Services in Tacoma, emphasized the precariousness of the situation for those who miss their earned release date. Even if they have secured employment and housing prior to their release, these arrangements can easily unravel in the face of unexpected delays. Willie noted that there is no guarantee that someone will hold a job or a living space open for weeks or even a month while the individual awaits their eventual release.

Inmates have no legal means to challenge being detained for weeks or even months beyond their scheduled release date, as there are no statutes guaranteeing these dates.

Taxpayers bear the brunt of the delays, as monthly expenses can differ widely among prisoners. According to the department’s estimates, the cost per inmate per month was around $5,300 as of 2022. This implies that in the last fiscal year, the DOC spent approximately $7 million detaining inmates beyond their release dates.

Although the DOC did not provide a response to the criticisms regarding the reasons for the delays, the agency acknowledges that the delays are indeed widespread and frequent. The administrators emphasize that certain factors that contribute to the delays are beyond their control. For instance, it is challenging to find appropriate housing for individuals who have been released from prison even under normal circumstances, let alone during a period of severe statewide housing scarcity.

According to the Department of Corrections, inmates convicted of sex offenses may be held past their release date until deemed rehabilitated by Washington’s Indeterminate Sentence Review Board, which oversees their sentences. Approximately 10% of those released late in fiscal year 2023 were individuals convicted of sex offenses, as per data provided by the DOC.

According to reentry service providers and prison counselors, the delays could be reduced if policymakers and administrators hold DOC staff accountable for missed deadlines. They suggest eliminating bureaucratic communication barriers and providing counselors with better resources to manage their caseloads.

Jacob Schmitt, a consultant with the state’s Office of Public Defense who focuses on clemency and postconviction relief efforts, stated that the issue of lengthy sentences has persisted for years. Schmitt’s personal experience with the matter led to his own release from prison last year after his sentence for a 2014 burglary was reduced by the court.

Schmitt emphasized the importance of gauging expenses against liberty, stating that every day matters.

‘There are seldom repercussions’

According to reentry support providers in Washington, the primary cause of delays is often attributed to slow-moving counselors or communication issues within the department. They suggest that implementing stricter deadlines for staff and improving communication systems could significantly reduce these delays.

According to DOC counselors who spoke with InvestigateWest, their colleagues who fail to meet deadlines or neglect inmates on their caseload are not held accountable. However, they also explained that the root cause of this issue is the excessive workload, ambiguous job descriptions, and high turnover rates, which make it challenging to bring about substantial improvements.

The reason behind the delays, as stated by both groups, is the approval process for release addresses.

The Department of Corrections mandates that inmates who are required to serve a period of community supervision, which is similar to probation, must obtain an approved release address before their release from prison. Many inmates intend to move in with their family after their release, while others opt for the department’s housing voucher program, which provides $700 per month for up to six months, and plan to rent a bed from a transitional housing provider.

A community corrections officer is responsible for visiting a release address and evaluating whether it is safe and appropriate for the inmate’s situation before granting approval.

Community corrections officers only allow inmates to submit one address at a time for approval. If the officer decides that the initial address is not a suitable fit, the inmate must start the process again, which can set them back for weeks or even months.

After their release address gets approved, inmates convicted of violent crimes and sex crimes face one final hurdle – a public notice of their release to be issued at least 30 days before their departure from custody. Advocates argue that this notice creates another chance for delays.

The Department of Corrections has established specific timelines for each stage of the process, with community corrections officers given a month to review most residential addresses. However, the enforcement of these deadlines is left up to the discretion of prison supervisors.

According to Chris Wright, a spokesperson for the DOC, counselors are responsible for overseeing their caseloads and ensuring that all required reentry planning work is completed.

According to the spokesperson, when a counselor falls behind, supervisors are promptly notified. In such cases, the supervisors take action and hold the staff members accountable for not meeting the performance expectations. This includes conducting performance reviews to ensure that the counselors are meeting the required standards.

According to Willie, a case manager with Native American Reentry Services, some counselors often neglect their duties by missing deadlines and failing to communicate with the inmates on their caseload. Having been released from Washington’s prison system in 2015, Willie has personally witnessed such negligence on the part of counselors.

“He didn’t even bother to inform me that he was going on vacation, and I was supposed to be released,” he expressed. He further added, “The counselors are supposed to start working with the inmates six months before their release date. However, if the counselor fails to dedicate enough time to them or misses out on any important paperwork, the inmates may not be able to get out on schedule.”

According to Jeanette Young, a counselor at the Washington Corrections Center in Shelton, some supervisors tend to turn a blind eye when counselors fail to meet their planning deadlines in certain units.

According to her, there’s a cohort of individuals who frequently skip work without facing any consequences. “We rarely see any disciplinary action being taken,” she remarked.

Young stated that when colleagues fail to show up to work without prior notice or fall behind on their responsibilities, it puts additional pressure on the more hardworking counselors to compensate for the lack of effort.

According to her, the DOC has recruited “reentry navigators” to support prisoners participating in the graduated reentry program. This program enables inmates to serve their sentences in a partially confined setting.

According to her, although they are expected to be involved in the reentry planning process, nothing has been taken off their plate.

Teamsters 117, which is Young’s union, has been facing a major setback as the navigators are not a part of it. As a result, they are usually unable to operate within prisons, which restricts their capacity to assist overburdened counselors. To address this issue, Teamsters 117 has been in talks with the DOC to incorporate the navigators into their bargaining unit.

According to Young, one crucial aspect to address the delays is to expand the state’s transitional housing options. She stresses that the number of residences available to those who receive housing vouchers has not seen a significant increase in recent times.

According to some providers of reentry housing, the lack of attention and organization from DOC counselors worsens the difficulties posed by the housing shortage in the state.

According to Jim Chambers, a recruitment and retention manager at Weld Seattle, a nonprofit transitional housing provider, the counselors at DOC are often hesitant to start arranging release addresses early enough for partners to plan properly. Chambers clarified that he was sharing his personal experience and not representing his employer.

According to the speaker, housing providers could consider renting a house for 10 women who will be released in three months. He suggested that their organization’s funds could be used along with the women’s vouchers to cover the remaining costs. He emphasized the importance of planning ahead, as it would allow for more beds to be made available. However, he expressed his frustration that counselors often wait until two months before a person’s release date to start planning, which does not leave enough time to find suitable housing in a competitive market.

According to George Block, the reentry manager for Oxford Houses, which is a type of sober living home in central and eastern Washington, counselors at the Washington Corrections Center often experience delays.

Block shared that he typically receives a call from Shelton three weeks before a person’s release date, which he finds to be quite late. He mentions that he has been in touch with people from other prisons who provide him with six weeks’ notice. Despite the urgency expressed by some callers, Block cannot always accommodate them as most of the available beds at his facility are already occupied.

According to Young, communication barriers are prevalent among housing providers and Oxford Houses. She points out that the issue goes both ways, as some housing providers tend to neglect phone calls and emails. Furthermore, some Oxford Houses schedule interviews for potential residents at times that conflict with the required presence of counselors.

A potential fix

Washington public defenders have identified the Washington Corrections Center in Shelton as the facility with the highest number of delays as well as the longest delays. However, they also believe that this facility could offer the most potential for reducing delays.

InvestigateWest analyzed DOC data and found that in fiscal 2023, the prison served as the final destination for 25% of individuals released from DOC custody. Furthermore, it was responsible for almost one-third of all delayed releases.

In any Washington DOC facility, inmates who are held past their release date experience a median delay of just under a month. However, the situation is even worse at Washington Corrections Center, where the median delay can extend to over a month and a half.

Current inmates and reentry support providers are not surprised by these statistics.

Tomas Keen, an inmate at the prison, has expressed his frustration with the facility, stating, “This facility has a culture of incompetence.” Keen, who has been in custody since 2010 for assault, vehicle theft, and unlawful possession of a firearm, has had experience in six of the state’s prisons. He has also completed paralegal training courses and now offers legal advice to other inmates, including those who remain in prison despite having completed their earned release dates.

According to him, there is a common complaint about being overworked and understaffed. He pointed out that the number of counselors per unit at the current facility seems to be the same as it was at Stafford Creek Corrections Center, where he did not witness such problems.

According to Keen’s estimations, the counselor-to-inmate ratios are predominantly correct. The Washington Corrections Center had a higher number of inmates per counselor than the average prison in Washington during fiscal years 2022 and 2023. However, as of fiscal year 2024, the Shelton prison has approximately 20% fewer inmates per counselor than the median prison.

According to the counselors at the prison, the idea of a “culture of incompetence” is not accurate. They claim that even the most diligent counselors are not given the necessary resources to succeed. While recognizing the challenges at the Washington Corrections Center, counselor Young also highlighted that the prison’s layout makes it difficult to be efficient. She shared that she doesn’t have a consistent office space and has to spend a significant portion of her day searching for a place to take calls. This process can involve walking a quarter-mile between her unit and the administration building, even in harsh weather conditions. Young suggested that having a dedicated office for counselors would free up time in her schedule, allowing her to work more closely with the inmates.

The reason for the majority of delays at Washington Corrections Center is due to its distinct position within the state’s prison system.

Over half of the prisons in Washington state are located in or near the Olympic Peninsula. The Washington Corrections Center, for instance, is situated in a central location on the southwest corner of the peninsula, across from a clearcut on an otherwise empty stretch of rural highway.

The receiving center at the prison serves as a transfer point for male inmates who are being moved between prisons or transferred from a county jail to DOC custody. However, the facility has been known to draw attention due to overcrowding and limited amenities.

Castillo, who was transferred to the intensive management unit in 2019, recalls his time spent in the receiving center where he noticed a violation of the two-man cell policy. He shares, “It’s supposed to have two-man cells, but we had a guy on the floor, too – his face was pretty much next to the toilet.”

In fiscal 2023, the Washington Corrections Center’s receiving center contributed to the release of one out of every six individuals after their earned release dates. Shockingly, around 50% of inmates released from this center missed their earned release dates during the same period.

Upon their transfer to prison, numerous receiving center inmates have already spent several months in jail waiting for their trial. This period is usually deducted from their sentences by the courts. As a result, those who are convicted of lower-level felonies arrive at the Washington Corrections Center with a minimal amount of time to develop a reentry plan before their release date.

Keen explained that if someone is sentenced to a year and a day in prison, and they have already spent eight months in jail awaiting judgment, they will receive time served credits. However, by the time they arrive at Shelton, they may have already passed their earned release date.

According to Young, who is employed in the receiving center, the prison’s system for identifying inmates who arrive on or shortly before their release date is not functioning as intended.

According to Young, even when an inmate on her caseload needs to be fast-tracked, she doesn’t receive any notification for it. Instead, the notifications are sent to supervisors who may or may not pass on the message. In some cases, the notifications go to staff who are no longer involved in reentry planning, having switched jobs months ago.

According to Young, the position for “quick releases” within the receiving unit has been vacant for over a year. She pointed out that the high turnover rate among counselors, supervisors, and administrators can hinder attempts to tackle case backlogs and delays.

Over the past few years, defense lawyers have made efforts to prevent their clients from getting stuck in the receiving units by avoiding the transfer to DOC custody. They have been arranging for inmates to be released directly from jail, thereby bypassing the quagmire altogether.

The success of these efforts has largely depended on “paper commits,” which are ad hoc agreements made with prosecutors, courts, and the DOC.

Sheri Oertel, an attorney specializing in felony cases at the Washington Defender Association, explains that a delay in transport to the Department of Corrections is essentially a court order. During this time, the individual can sort out their credits for time served and complete their release planning. This allows for a direct release from jail.

According to Young, while paper commits are a rare occurrence, standardizing the practice could be a practical solution to minimize delays in releasing products.

According to her, it is essential to collaborate with individuals in county jails. She believes that even if they can initiate the process in jails, it will reduce the waiting time in the receiving units.

According to Wright, standardizing the process of paper commits is a highly complex and challenging task, and the DOC is yet to take an official stance on it.

Simplifying the paper commit process is a challenging task due to the technological barriers. The DOC and county jails use different filing systems, and a significant amount of records are still maintained on paper. The synchronization of state and county systems would require a considerable amount of time and money.

According to State Senator Claire Wilson, it’s high time for those updates to be made. She stated, “We are still relying on manila envelopes far too much,” and emphasized the importance of investing in these upgrades.

‘Ninety-seven percent’

Wilson presented a bill last year that aimed to increase the assistance provided to individuals leaving prison. This bill would have mandated the Department of Corrections (DOC) to develop release plans 12 months before the person’s release date. Although Wilson did not know the extent of the delays at the time of introducing the bill, she acknowledges that initiating planning earlier could potentially decrease the number of delays.

The portion of the bill that required the DOC to release nonviolent offenders early due to the coronavirus pandemic was later vetoed by Gov. Inslee. In his explanation, he cited the limited capacity of the DOC and the expenses involved in providing additional release planning steps. However, the governor did approve a part of the bill that mandates the DOC to provide inmates with a 90-day supply of their prescribed medications upon release.

According to reentry support providers, the state could save a significant amount of money by reducing delays. “Holding people past their earned release date costs millions of dollars every year, and this is something that should concern everyone,” stated Schmitt, who works as a contractor with the state’s Office of Public Defense. Wilson emphasizes that the public should also consider the costs incurred by individuals who are kept in custody beyond their scheduled release dates.

According to the state senator, nearly all incarcerated individuals will eventually return to their communities. Therefore, it is crucial to provide them with the necessary tools and resources to plan a successful reentry and avoid committing further crimes.

As an example of the alternative, Castillo, a man from Okanogan County who was released from the Washington Corrections Center in 2019, offers himself.

Castillo remains uncertain about the reason behind his extended detention beyond his scheduled release date. Due to his brief sentence, he had limited chances to converse with counselors about his release plans. Additionally, his sentence did not entail any community custody period, which meant that he was not required to provide an approved address. From what he could gather, he believes that the delay was a result of inadequate communication, either between the counselors or between the Department of Corrections and Okanogan County.

He expressed feeling forgotten, stating, “It felt like they just forgot about me.”

According to Schmitt, the reasons behind the delayed release of Castillo are not mysterious. He stated that it is not surprising for someone in the intensive management unit to not be treated as a priority. Inmates in this unit do not have access to kiosks to check updates on their earned release date, unlike those in the general population units.

According to him, the counselor should be responsible for keeping him informed, but they might simply forget to do so. He also mentioned that there seems to be a lack of concern for individuals in the intensive management unit.

In 2019, when Castillo was released from the Washington Corrections Center, he stayed with his grandmother for a short time. However, he found this arrangement to be precarious and lacking in the necessary support he required to keep himself out of trouble.

He stated, “I am a recovering addict and had no means to strategize my move into a sober living house or plan my treatment.”

In the months that followed, he faced difficulties in securing employment to assist his grandmother in paying for rent and utility bills. Unfortunately, he eventually succumbed to his addiction and ended up back in Okanogan County jail for stealing a car.

Castillo is set to return to the Washington Corrections Center later this year, in preparation for his release.

He emphasized the importance of planning, stating that not having a plan sets one up for failure which can lead to repeated attempts.

InvestigateWest, an independent news nonprofit that focuses on investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest, can be reached at [email protected], according to reporter Paul Kiefer.